Developing walking infrastructure shouldn’t just be about positioning a pavement at the edge of the road. Pavements are an integral part of our transport infrastructure, carrying a huge proportion of all of our everyday journeys – just over 10% of journeys to work were made by foot at the last census (2011). The walking environment is also often our treasured parks and public open spaces and the quality of these can vary across the city. However, this is a figure that’s in decline and steps need to be taken to ensure that walking is the most obvious choice for short journeys for utility and leisure across Bristol.

However, pavements are rarely planned, they’re often under-maintained when compared with the roads the run alongside and they’re far from continuous. Think about the number of times when walking in the urban environment that you have to ‘stop, look, listen’ before crossing a side road, or wait for ages for a green man at a crossing that was meant to make your journey better. Pedestrians after all should have priority at side road crossings over a turning vehicle, but only AFTER they’ve started to cross. The onus is on the vulnerable user to be mindful of the presence of the dominant user. People on foot sit at the top of our transport hierarchy, followed by people on bikes, then buses and other transport. All transport schemes should be considered on the impact on those modes in that order – and yet, we often see the reverse of this with increasing pressure to reduce congestion and its harmful impacts, pavements can be narrowed to increase car lanes, or where pavements are widened, it’s often to accommodate cycling – pinching more space from people on foot.

Yet there are some great examples of where people on foot are getting a better deal, and their place at the top of the user hierarchy. This is particularly evident at side road crossings, where the term ‘invisible’ junction springs to mind. As such, unless you’re looking for it, to all intents and purposes, the junction isn’t there.

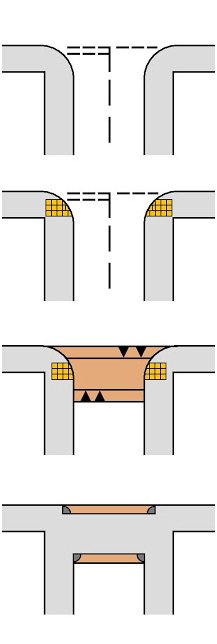

In Figure 1, we’ve borrowed a diagram from The Ranty Highwayman whereby in the first two examples we’ve slowly seen the adoption of features like flush kerbs to enable wheelchair, mobility scooter and buggy access at junctions and crossings, and tactile paving warnings for blind and partially sighted people.

In some cases, as in the third example, there might be a raised table to slow the entry speed of a vehicle into a side road and avoid the need for the person crossing to drop to the road level to cross.

However, in the fourth example the pavement is clearly continuous, and has priority over the turning traffic. The onus for taking care at the junction in this instance would clearly be on the vehicle driver.

This is a real-life example (use this link for Google street view):

Jon Usher (Sustrans)